This text was featured within the One Story to Learn At the moment e-newsletter. Join it right here.

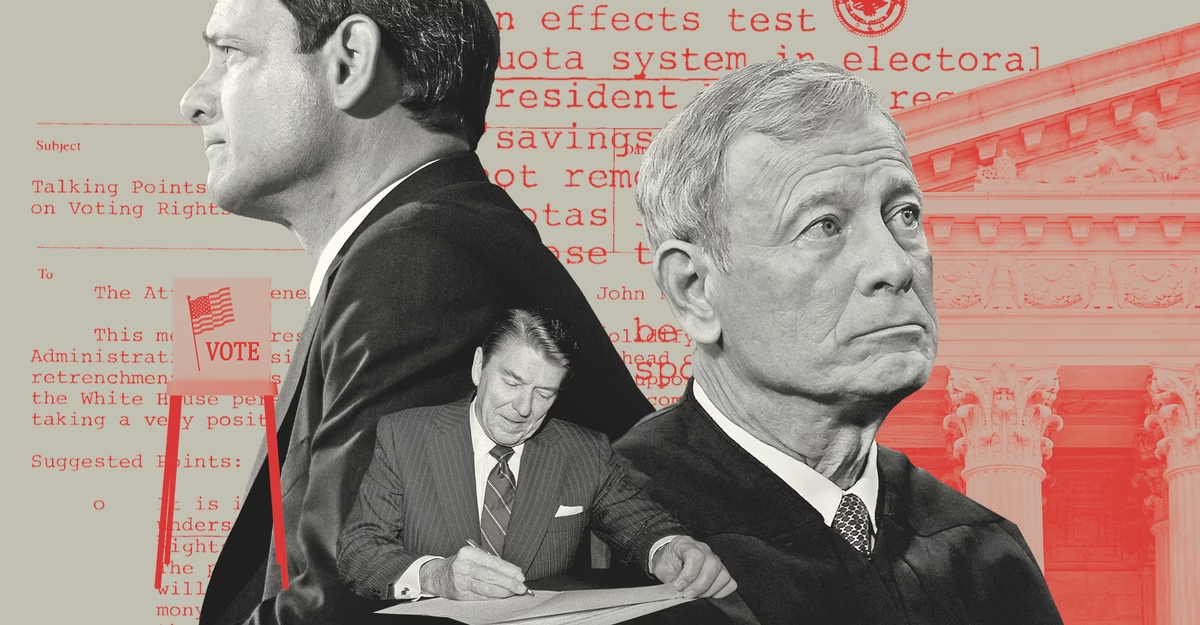

In 1982, when the Voting Rights Act was up for reauthorization, the Reagan Justice Division had a purpose: protect the VRA in title solely, whereas rendering it unenforceable in observe. A younger John Roberts was the architect of that marketing campaign. He might quickly get to complete what he began.

Final month, on the oral argument in Louisiana v. Callais, a majority of the conservative justices appeared to sign their willingness to forbid any use of race information in redistricting. That might result in the tip of the VRA’s Part 2 protections for minority voters, and permit states throughout the South to redraw congressional districts at the moment represented by Black Democrats into whiter, extra rural, and extra conservative seats, doubtlessly earlier than the 2026 midterms.

A central query of the case, hotly debated throughout oral arguments, is whether or not Part 2 ought to prohibit election legal guidelines and procedures which have a racially discriminatory impact, or simply these handed with clear racially discriminatory intent. Roberts nearly definitely had flashbacks. This is similar query that was on the heart of the 1982 reauthorization struggle. Again then, the longer term chief justice’s job was to design the Division of Justice’s VRA technique.

When Roberts first arrived at DOJ in 1981, contemporary off a clerkship for William Rehnquist on the Supreme Courtroom, he was assigned two essential portfolios: prepping Sandra Day O’Connor for her affirmation hearings and voting rights. O’Connor sailed by way of the Senate. The VRA could be extra contentious: A 1980 Supreme Courtroom resolution in Metropolis of Cellular v. Bolden had required plaintiffs making a Part 2 declare to show that lawmakers had racial-discrimination intent. That’s tough to display, and it introduced practically all Part 2 litigation to a halt.

Civil-rights teams, Democrats, and reasonable Republicans needed to make use of the VRA reauthorization to override Cellular and make clear that Congress clearly meant to treatment all racially discriminatory results. The Reagan administration was divided. Average Reaganites didn’t need to battle over the landmark regulation, which was common. Ideological conservatives inside DOJ spoiled for a struggle. They have been content material to increase the act, simply as long as it was inconceivable to make use of. Roberts led the way in which.

Roberts’s papers from this period, housed on the Nationwide Archives, present his dedication and dedication. They embrace memos and speaking factors, draft op-eds, scripted solutions for bosses to ship in conferences and earlier than Congress, and shows he gave to senators and Hill employees. These recordsdata present how Roberts devised the messaging methods that made it doable for the administration to assert it supported the VRA, whereas really serving to to neuter it—an method he has since mastered as chief justice.

When Roberts began as a particular assistant to Lawyer Common William French Smith at DOJ in August 1981, pragmatic White Home aides who needed to keep away from the messiness of a voting-rights struggle appeared to carry the successful hand. Earlier that summer season, the conservative consultant Henry Hyde had skilled one thing of a conversion after public hearings throughout the South, reversed his personal place, and urged his outdated buddy Ronald Reagan to return aboard. Reagan addressed a nationwide NAACP conference that June and vowed he would by no means enable limitations to be positioned between any citizen and the poll field. By August, he informed The Washington Star that he would again no matter 10-year reauthorization Congress despatched him, punting the query of intent versus results to lawmakers.

However that fall, because the White Home deliberate to launch an announcement confirming that Reagan would help no matter compromise Congress reached, DOJ pushed again exhausting. The lawyer basic demanded a gathering with Reagan. Following the assembly, Reagan embraced two of Smith’s proposals—sustaining the intent normal, and making it simpler for localities to flee Part 5 preclearance, which required all our bodies in coated states to get approval earlier than making any modifications to election regulation or procedures. (Roberts would successfully finish that requirement along with his resolution in 2013’s Shelby County v. Holder, neutering the regulation by freezing the method that decided which states have been coated.)

Reagan now declared the results normal “new and untested”—a place that hewed nearly verbatim to Roberts’s speaking factors. In his end-of-year information convention, Reagan channeled Roberts once more. The impact rule “might result in the kind of factor by which impact could possibly be judged if there was some disproportion within the variety of officers who have been elected at any governmental degree,” Reagan mentioned. “You might come all the way down to the place all of society needed to have an precise quota system.”

That is nearly precisely what Roberts would write in his December 1981 memo titled “Why Part 2 of the Voting Rights Act Ought to Be Retained Unchanged”: “Incorporation of an results check in §2 would set up basically a quota system for electoral politics.” Then got here the road that could possibly be seen as defining many years of future jurisprudence: “Violations of §2 shouldn’t be made too straightforward to show, since they supply a foundation for probably the most intrusive interference conceivable by federal courts into state and native processes.”

Roberts impressed Reagan’s shift. His phrases and concepts made up the core of the president’s statements. He positioned the administration into an intent-versus-effects struggle that Reagan’s political counselors thought pointless.

The subsequent battle could be earlier than the U.S. Senate. Roberts would script that too.

The Senate debate had kicked off with a mid-November New York Occasions op-ed from Vernon Jordan, then head of the Nationwide City League, titled “Diluting Voting Rights.” Roberts should not have appreciated what he learn. Reagan’s endorsement of the intent normal “was not solely a political mistake,” Jordan wrote, however a “disservice” to conservatism. Then the civil-rights chief lowered the increase. Intent to discriminate, he wrote, is inconceivable to show.

“Native officers don’t wallpaper their places of work with memos about prohibit minority-group members’ entry to the polling sales space,” Jordan wrote. “Discriminatory results, nonetheless, are clear to all.” Proving intent, he argued, shifted and required the burden of proof and required proof that “could be nearly inconceivable to assemble.”

“The President’s endorsement of the Voting Rights Act,” he concluded, “is a sham.”

Roberts rapidly drafted a counterattack and circulated it to DOJ higher-ups. The pugnacious response insists that the intent check would make a “radical change” to the Voting Rights Act and slams the Home model as a “radical experiment.” Roberts conceded that native officers won’t wallpaper their places of work with racist memos, however insisted that “circumstantial proof” would nonetheless suffice, “as Mr. Jordan presumably is aware of.”

“The one ones who could possibly be disillusioned by the President’s actions,” Roberts held, “will not be these really involved about the suitable to vote however fairly those that, for no matter motive, have been merely spoiling for a struggle,” fiercely attacking the integrity of a person who had devoted his life to the battle for civil rights.

Roberts’s viewers wasn’t civil-rights leaders or New York Occasions readers. The DOJ staff wanted to maintain the variety of Senate proponents for the intent check under 60, the edge for defeating a filibuster. Senator Strom Thurmond chaired the Senate Judiciary Committee. Opponents of the VRA’s results provision felt assured that they might engineer a number of obstructionist feints and amendments to dam its passage. So it shocked them when Senator Charles Mathias, a Republican, filed his invoice, which included the results check, with 60 co-sponsors. If the coalition of 40 Democrats and 21 Republicans held, the reauthorization would move simply. Thurmond sputtered in disbelief when knowledgeable of the quantity: “They have to not have learn the invoice!”

A surprised Roberts ready to struggle on. “Don’t be fooled by the Home vote or the 61 Senate sponsors of the Home invoice into believing that the President can’t win on this challenge,” Roberts wrote in a January 1982 memo to the lawyer basic. Roberts’s allies have been segregationists, his math was unhealthy, and his political instincts worse, however he urged his troops onward, assured in his personal evaluation of Congress. “Many members of the Home didn’t know they have been doing greater than merely extending the Act, and several other of the 61 Senators have already indicated that they solely meant to help easy extension,” he wrote. “As soon as the senators are educated on the variations between the President’s place and the Home invoice, and the intense risks within the Home invoice,” Roberts insisted, “strong help will emerge for the President’s place.”

Roberts labored each angle. The Senate Judiciary Committee was an opportunity to teach senators. The day earlier than the lawyer basic was scheduled to testify, the administration abruptly requested for a delay. Roberts remained centered. On January 25, 1982, he despatched Smith a memo of seemingly questions and prompt solutions to assist information his remarks. In his behind-the-scenes temporary to his boss, it’s obvious that Roberts was not prepared to countenance a single enchancment to the VRA.

Within the temporary, in detailing his objections to the results check, Roberts provided a tendentious account of supposed open-minded inquiry that pointedly ignored the testimony of consultants and misrepresented the phrases of civil-rights leaders. He endorsed Smith to inform Congress that “in reviewing the Voting Rights Act final summer season in the middle of getting ready suggestions to the President, I met personally with scores of civil rights leaders.” Roberts wrote, “The one theme from these discussions was clear: the Act has been probably the most profitable civil rights laws ever enacted and it ought to be prolonged unchanged. Because the outdated saying goes, if it isn’t damaged, don’t repair it.”

Right here Roberts was merely parroting an earlier speaking level he’d circulated through the Home debate; it had nothing to do with the precise views of civil-rights leaders who, in actual fact, have been decided in any respect prices to restore the faulty Cellular resolution.

His memo inspired Smith to double down on unfastened discuss of racial quotas earlier than Thurmond’s committee, contending with none empirical backing that the results check “would set up a quota system for electoral politics”—right here he underlined quota system—which “we imagine is essentially inconsistent with democratic ideas.”

The subsequent day, January 26, Roberts once more urged Smith to stiffen his resolve on the results query because the lawyer basic ready to start his testimony. Roberts additionally attended an important assembly on the White Home the place DOJ officers sought to shore up Reagan’s opposition to the results check—“as soon as and for all,” a seemingly pissed off Roberts wrote.

In this last prehearing memo, the younger aide exhorted his boss: “I like to recommend taking a really optimistic and aggressive stance.” Roberts definitely adopted that recommendation; he had grown weary of all of the bureaucratic skirmishing with Reagan’s political staff, and demanded that the White Home “actively work” to enact DOJ’s most popular coverage. He insisted his place could possibly be bought politically. “The President’s place is a really optimistic one,” Roberts wrote, repeating his pet mantra. “If it isn’t damaged, don’t repair it.”

In his memos, Roberts maintained that the results check would “throw into litigation current electoral techniques at each degree of presidency nationwide when there isn’t any proof of voting abuses nationwide supporting the necessity for such a change.” Roberts additionally once more sought to tie opposition to the results check to the administration’s total stance on race and affirmative motion. “Simply as we oppose quotas in employment and training, so too we oppose them in elections.” Roberts concluded, imperiously, “It is extremely essential that the struggle be received, and the President is absolutely dedicated to this effort. His employees ought to be as nicely.”

Nobody might query Roberts’s dedication. That day he despatched Smith yet one more memo, a two-page response to an editorial in The Washington Publish that endorsed the results check. Then, in an early February 1982 memo to his direct boss, Brad Reynolds, Roberts provided handwritten edits on a draft op-ed. “I don’t agree with the Lawyer Common that it’s essential to ‘discuss down’ to the viewers,” Roberts proclaimed. “The frequent writings on this space by our adversaries have gone unanswered for too lengthy.”

Roberts remained hopeful that his place would prevail within the Senate, both by placing the filibuster again in play, enabling a presidential veto, or slowing issues down sufficiently with a view to achieve a negotiating cudgel because the VRA neared expiration. No matter obstructionist imaginative and prescient beguiled him most, Roberts labored the Senate exhausting. He assembled clips of op-eds aligned along with his facet alongside along with his “Why Part Two of the Voting Rights Ought to Be Retained Unchanged” essay to be despatched to pleasant places of work. He ran all this previous Ken Starr—then a counselor to Smith, 16 years earlier than the Monica Lewinsky investigation—with a handwritten observe penned daringly on the lawyer basic’s letterhead: “Ken—potentialities to distribute to senators.” He signed it merely “John.”

Orrin Hatch’s Judiciary subcommittee—after 5 weeks of hearings centered nearly totally on intent versus results—started to fall into line. It preserved the intent normal within the Senate invoice, which then moved to Thurmond’s kingdom, the complete committee. By then, Senator Bob Dole had seen sufficient. The Kansas Republican was decided that the GOP be the occasion of Lincoln, not Thurmond. He quietly settled the matter: Part 2 would carry the results normal. The language of the accompanying Senate report couldn’t have been clearer. Racial results could be sufficient. Dole knowledgeable Reagan that DOJ might proceed to struggle—however they’d lose. He had at the very least 80 votes.

Again at Justice, Roberts’s band of brothers didn’t seethe a lot as they threw up their arms in resignation. “The Reagan administration took the principled view over the politically advantageous,” Michael Carvin, the famed conservative litigator who served at DOJ with Roberts, informed me, “after which they ultimately caved.”

A unique technique could be wanted. That April, as Roberts and others at DOJ battled, younger conservative regulation college students, joined by mentors resembling Robert Bork and Antonin Scalia, would have the first nationwide gathering of what would turn out to be referred to as the Federalist Society at Yale Legislation. Conservatives got here to a brand new conclusion: If you wish to change the regulation, change the judges.

Greater than 20 years later, about to ascend to the excessive courtroom, Roberts would brush apart issues about his views on voting rights by suggesting that the 1982 struggle was a youthful folly, and that he had simply been doing his job. “Senator,” Roberts informed Russell Feingold, a Wisconsin Democrat, “you retain referring to what I supported and what I needed to do. I used to be a 26-year-old employees lawyer. It was my first job as a lawyer after my clerkships. I used to be not shaping administration coverage. The administration coverage was formed by the lawyer basic on whose employees I served. It was the coverage of President Reagan. It was to increase the Voting Rights Act with out change for the longest interval in historical past at that time, and it was my job to advertise the lawyer basic’s view and the president’s view on that challenge. And that’s what I used to be doing.”

This was not totally correct. As soon as once more, Roberts was masterfully playacting help for a regulation he labored to thwart. The consequences normal got here from DOJ. It was not initially the coverage of President Reagan. It was not the president’s view. Roberts had carried out way over what he claimed below oath. And when he and fellow younger Reaganite Samuel Alito arrived on the Supreme Courtroom, the arguments that had as soon as misplaced in Congress would now carry the day—not as a result of issues had really modified within the South, however as a result of the world moved to the judiciary.

Now John Roberts doesn’t want the president, 60 senators, or 218 representatives. 4 like-minded conservatives on the Courtroom could be sufficient. It seems there are 5—plus Roberts himself.

This text was tailored from David Daley’s e book, Antidemocratic.

While you purchase a e book utilizing a hyperlink on this web page, we obtain a fee. Thanks for supporting The Atlantic.

Leave a Reply