China now dominates in every technology that defines the modern world.

According to the Australian Strategic Policy Institute’s 2025 Strategic Technology Tracker, released last week, China leads in seven out of eight AI categories, 13 out of 13 advanced materials and manufacturing technologies, in all seven categories of defence, space, robotics and transportation, nine out of 10 in energy and environment and five out of nine in biotechnology, genes and vaccines.

China’s global technology ascendancy is pretty much total, yet it has only half the number of billionaires as the US and that number grew this year by only half as much, so how is this possible?

And China is supposedly a Marxist-Leninist society, and Karl Marx was very suspicious of technology, writing in Wage, Labour and Capital (1847): “The instrument of labour, when it takes the form of a machine, immediately becomes a competitor of the worker himself.”

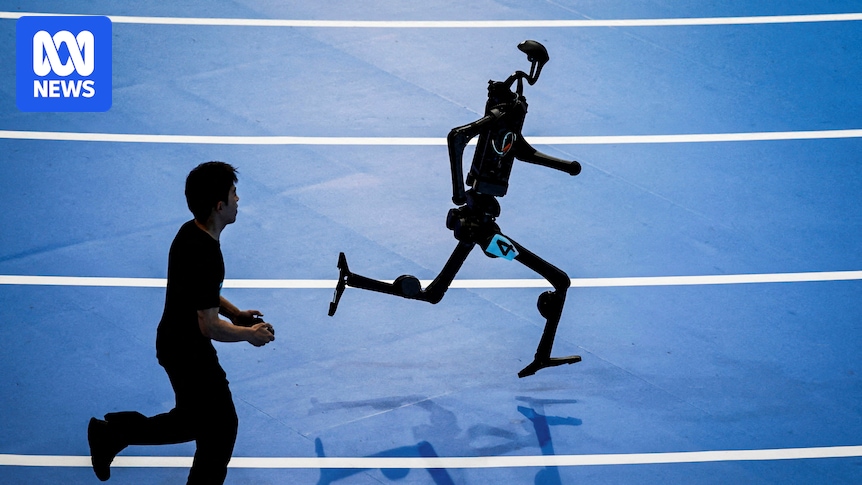

A Unitree Robotics humanoid robot at the inaugural World Humanoid Robot Games in Beijing earlier this year. (REUTERS: Tingshu Wang)

Can the West catch up?

No such qualms in the Chinese Communist Party, which is in charge of a country whose population of workers is declining.

The communists are driving the technology bus, not billionaires as in the US, and the few Chinese entrepreneurs who managed to amass a fortune serve at the pleasure of the party.

China’s arrival as tech supremo was on display last month at the 27th Hi-Tech Fair in Shenzhen.

It was 400,000 square metres (about 20 big cricket grounds) of dazzling technology (or so I read and saw on YouTube — I wasn’t there) with plenty of humanoid robots, including two of them slugging it out in a boxing ring behind that interview, and a whole zone dedicated to flying cars, or “eVOTL” vehicles (electrical vertical take-off and landing).

As Industrial Transition Accelerator executive Faustine Delasalle says: “There’s an acceleration in China that we’re not seeing in the rest of the world.”

China used to be trying to catch the West, specifically the US; then it caught up; now the West is trying to catch up to China, but likely can’t.

There are plenty of engineering marvels in China apart from those on display in Shenzhen last month.

Here’s a random list of a few things I’ve seen lately:

- a mosquito-sized drone for surveillance operations

- a mountain in Guizhou covered with solar panels

- cancer therapy research that disguises a tumour as pork, so the immune system attacks it

- an open-source AI model outperforming the best human score in the maths Olympics

- humanoid robots being shipped to industrial customers, according to the company

- a robot designed to clean hotel rooms and bathrooms

- 48,000 kilometres fast rail, with 350km/h top speed, including the Shanghai Maglev (magnetic levitation) which goes at over 400km/h

- the world’s highest bridge — the Huajiang Canyon Bridge

China ‘ditches the standard innovation model’

Analyst Dan Wang explains what’s behind all this in a book titled Breakneck — China’s quest to engineer the future.

He explains that China is an engineering state, which can’t stop itself from building, while America is a lawyerly society which “has a government of the lawyers by the lawyers and for the lawyers” … and “blocks everything it can”, although Donald Trump is bulldozing regulations now.

“As the United States lost its enthusiasm for engineers, China embraced engineering in all its dimensions,” Wang says.

An aerial photo shows more than 60,000 solar photovoltaic panels installed on a barren mountain in Jinhua, Zhejiang province, China. (AFP: Yuan Xinyu)

China’s government spends hundreds of billions of dollars on what it calls a “whole of nation” industry policy, which began with “Made in China 2025” unveiled 10 years ago, and morphed into the 14th five-year plan in 2020 committing US$1.4 trillion over five to six years on new infrastructure, including 5G networks, smart cities, and industrial digitalisation.

Blogger Noah Smith described what “whole of nation” means in a post last week: “Essentially, what China has done is to ditch the standard innovation model, where government, academics, corporations, and financiers all work independently toward their own goals, and to replace it with a model where the government coordinates their interaction toward a single overarching goal from beginning to end.

“Basically, the government now tries to take innovation ‘from bean to bar’, as the chocolate shops say.

“It tries to identify a technological goal — say, becoming nationally self-sufficient in robotics — and then work backwards to figure out what breakthroughs it needs in order to reach that goal. Then it tries to fund the basic and applied research to create those breakthroughs, transfer the breakthroughs to the appropriate companies, help the companies create new products, and then help the companies commercialise and scale those products.”

The government works backwards from the goal for heaven’s sake! And then directs the basic research and funds the companies to create products and then to commercialise.

Now that’s what I call an industry policy! No wonder they’re ahead.

People try AR glasses during the World Artificial Intelligence Conference in Shanghai earlier this year. (REUTERS:Go Nakamura)

Australia’s ‘National AI Plan’ lacking

This approach has also led to China having a monopoly on critical minerals and rare earths needed for modern technology, giving them powerful geopolitical clout, now being wielded.

The downside to it is overcapacity, and now the government is trying to stop what’s called “involution” — that is, intense cut-throat competition with diminishing returns, characterised by price wars and oversupply in a crowded market.

Needless to say, the comparison of China with Australia is less flattering than the one with the United States. We’re not e-cycling on the same velodrome.

Last week, the Labor government launched its “National AI Plan”, which is more brochure than serious plan.

The main purpose of it seems to be not having the “10 guardrails” around AI that the previous science and industry minister, Ed Husic, was talking about last year.

Instead, there will be $30 million for an AI safety institute, which is fine, except I’m reading If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies, the book by Eliezer Yudkowsky and Nate Soares about the consequences of machine super-intelligence that is currently going viral, and which convincingly argues the case expressed by that rather arresting title.

If they’re right, $30 million doesn’t really seem enough to stop everyone dying.

That aside, the government money in the Australian National AI Plan devoted to promoting AI is explicitly all old money — $460 million of “existing funding already available or committed to AI and related initiatives”. Also, that’s over an unstated multiple of years, not one year.

The Chinese Government has spent US$56 billion directly supporting the development of AI in 2025 alone.

Loading

China holds key to modern world

So, China is in the process of supplanting the American hegemony, which is why the Trump administration is now referring to the US and China as “G2”.

It indicates the US has pivoted from a policy of aggressive decoupling and containment of China to one of transactional co-management, which presumably ends up with them dividing the world into two, leaving Asia Pacific to China.

The US had no choice: not only is China way too powerful to be messed with, it increasingly holds the key to the modern world.

In many ways, autocratic China is where democratic America was in 1944 when the Bretton Woods conference established its global hegemony.

China may soon absorb Taiwan, perhaps without firing a shot. America and the world will object, and likely do nothing, confirming a new global order.

There are many things wrong with China, but the implication of all this for Australia is clear: in a G2 world we must find a way to pivot.

Alan Kohler is finance presenter and columnist on ABC News and he also writes for Intelligent Investor.

Leave a Reply