There was never a single or simple reason that this Long Island kid and born-and-bred Yankees fan would choose Dale Murphy as a childhood idol.

He was the hero who found me and so many others on “SuperStation TBS” in the 1980s — the grace, the style, the smile, the power, the speed, the red-white-and-blue pullover jerseys, all etched in my boyhood memories. He was the all-American good guy on some pretty bad Atlanta Braves teams, a superstar on the field and off.

Murphy himself made my loyalty worthwhile many times over, through a lifetime of fandom and then ultimately friendship that, frankly, is still surreal to me.

That’s part of what’s driven an effort that also might not make a whole lot of sense. Despite a professional lifetime spent covering campaigns in political journalism, I’ve never been part of one until now — with the goal of getting Dale Murphy enshrined in the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

This Sunday, in a hotel conference room in Orlando,16 esteemed baseball minds will gather on the sidelines of Major League Baseball’s winter meetings to consider which of eight “modern era” retired players deserve plaques in Cooperstown.

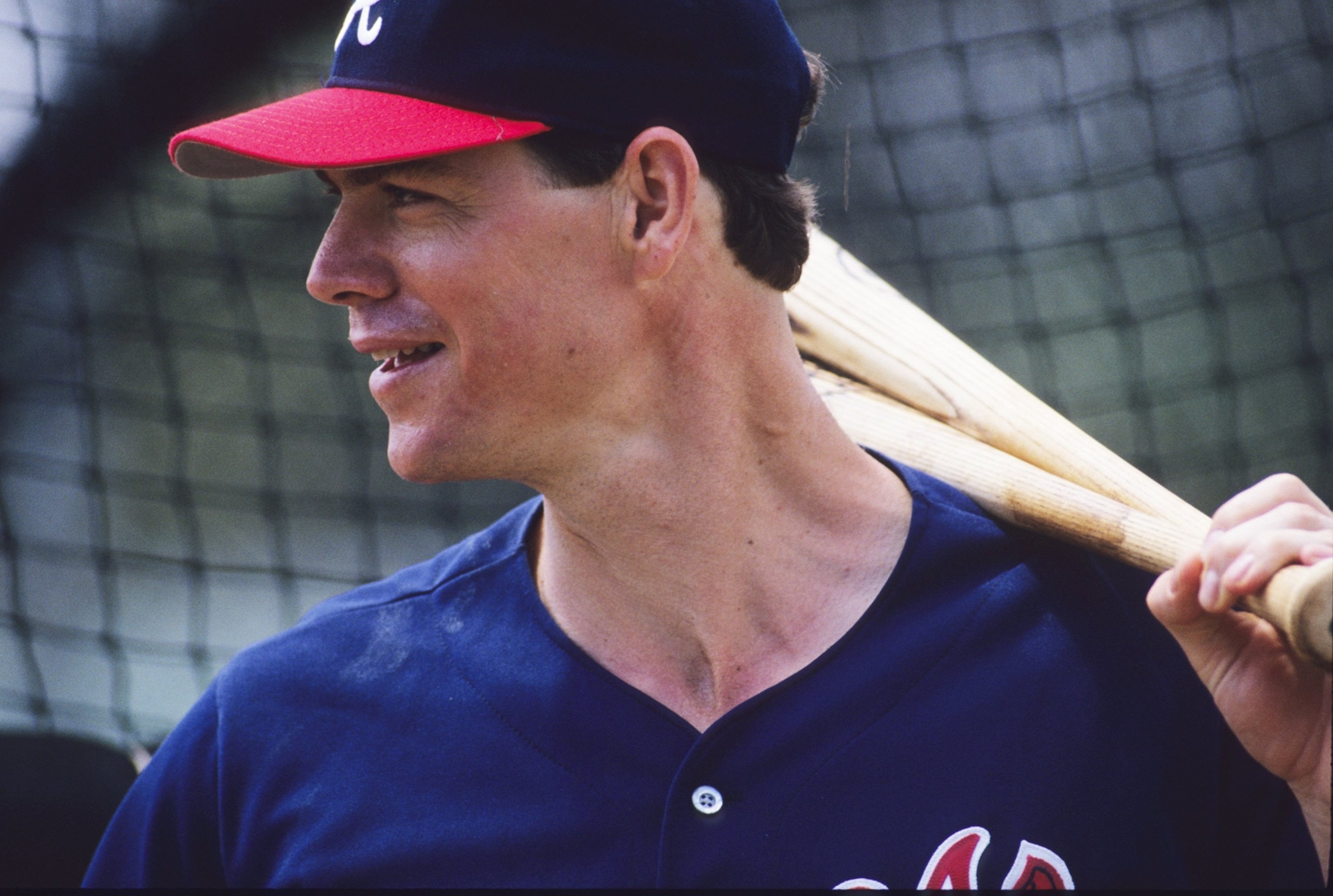

Dale Murphy #3 of the Atlanta Braves smiles for the camera in this portrait during photo day in spring training circa 1978.

Focus On Sport/Getty Images

It’s likely only one, two, or at most three of the eight — all legends on their own — make it in. Over the last few months, a legion of Murphy’s fans have come together to try to get Murphy in at last.

The effort has brought together country-music megastars and TikTok influencers, actors, rock stars, politicians, comedians, rappers, graphic artists, and some of the biggest baseball names around.

No matter what happens in the final vote, it’s already resonated in a way that’s deeply meaningful for Murphy’s countless fans, as well as the man himself.

“We’re a part of people’s memories,” Dale Murphy told ABC News, reflecting on the fan-driven effort in an interview that aired on “Nightline” Thursday. “The memory and the thing that people remember the most about your career is not necessarily you, but the memories and the feelings it brings to them about their family, and being able to enjoy the game of baseball with their family and their parents and their siblings.”

“It’s been humbling to us,” his wife, Nancy Murphy, told ABC News. “Seeing those fans from literally coast to coast.”

Dale Murphy #3 of the Atlanta Braves bats against the San Diego Padres during an Major League Baseball game circa 1982 at Jack Murphy Stadium in San Diego.

Focus On Sport/Getty Images

My contribution to that geography came from growing up in a New York suburb that was and remains Mets territory. My father passed down rooting for the Yankees to my brother and me, but I needed a National League team if for no other reason than to root against the colorful bad boys that were the ’80s Mets.

Flipping channels on the first cable package my family had, I stumbled across Braves games. Media mogul Ted Turner bought the team in part to provide programming for what he called his “superstation” in 1976. Later that year, shortly before I was born, Murphy — then a gangly catcher with an erratic arm and power at the plate — made his major league debut.

Turner branded the Braves “America’s Team,” swiping a marketing page from the Dallas Cowboys. It never really caught on, though for much of the ’80s, American households with cable could watch more Braves games than those of any other professional franchise.

This baseball-crazed kid with a contrarian streak discovered “Murph” around 1984, coming off his back-to-back MVPs and in the middle of a dominant streak with few parallels that decade.

Dale Murphy of the Atlanta Braves signing autographs in the locker room before a MLB game in 1985 in Atlanta.

Ronald C. Modra/Getty Images

Turner’s TBS helped create a national fan base for the Braves, though the Braves made the playoffs just once in the ’80s and collected more losses than any other National League franchise that decade.

They did have Murphy, by then moved to the outfield by the legendary manager Bobby Cox, with power, speed, agility, slick fielding, baseball smarts — plus quiet grace and a ready smile.

He was also, famously, a great guy. He was married to his college sweetheart with a family that seemed to grow with every magazine profile. (Dale and Nancy Murphy have eight kids and 20 grandchildren, plus three more on the way.)

Those profiles would often point out that Murphy endorsed milk and ice-cream brands but neither drank nor smoked, in accordance with his Mormon faith. I read his autobiography, collected his baseball cards and, when I was 12, talked my family into a trip to Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium.

Dale Murphy #3 of the Atlanta Braves during spring training, March 20, 1990, in West Palm Beach, Fla.

Ronald C. Modra/Getty Images

I stood behind a dugout during batting practice and yelled “Mr. Murphy” for 20 minutes. He signed my baseball, like he did for countless thousands of fans before and since, in what I told him at the time was the best day of my life.

Murphy’s career ended in 1993, after several injury-hobbled seasons in Philadelphia and Colorado. I was in high school and discovering things that had nothing to do with baseball.

By the time he was first eligible for the Hall of Fame, the seasons where he led the league with 36 or 37 home runs looked like deadball-era totals compared to the 60s and 70s sluggers were posting — aided by performance-enhancing drugs, as we would learn only later.

He retired with 398 home runs — 27th on the all-time home run list, with 24 of the 26 ahead of him at the time currently enshrined in Cooperstown. Now, almost 30 years after the dawn of baseball’s steroids era — juiced bodies having shredded the record books — Murphy is 62nd on the all-time list, and still on the outside of the Hall looking in.

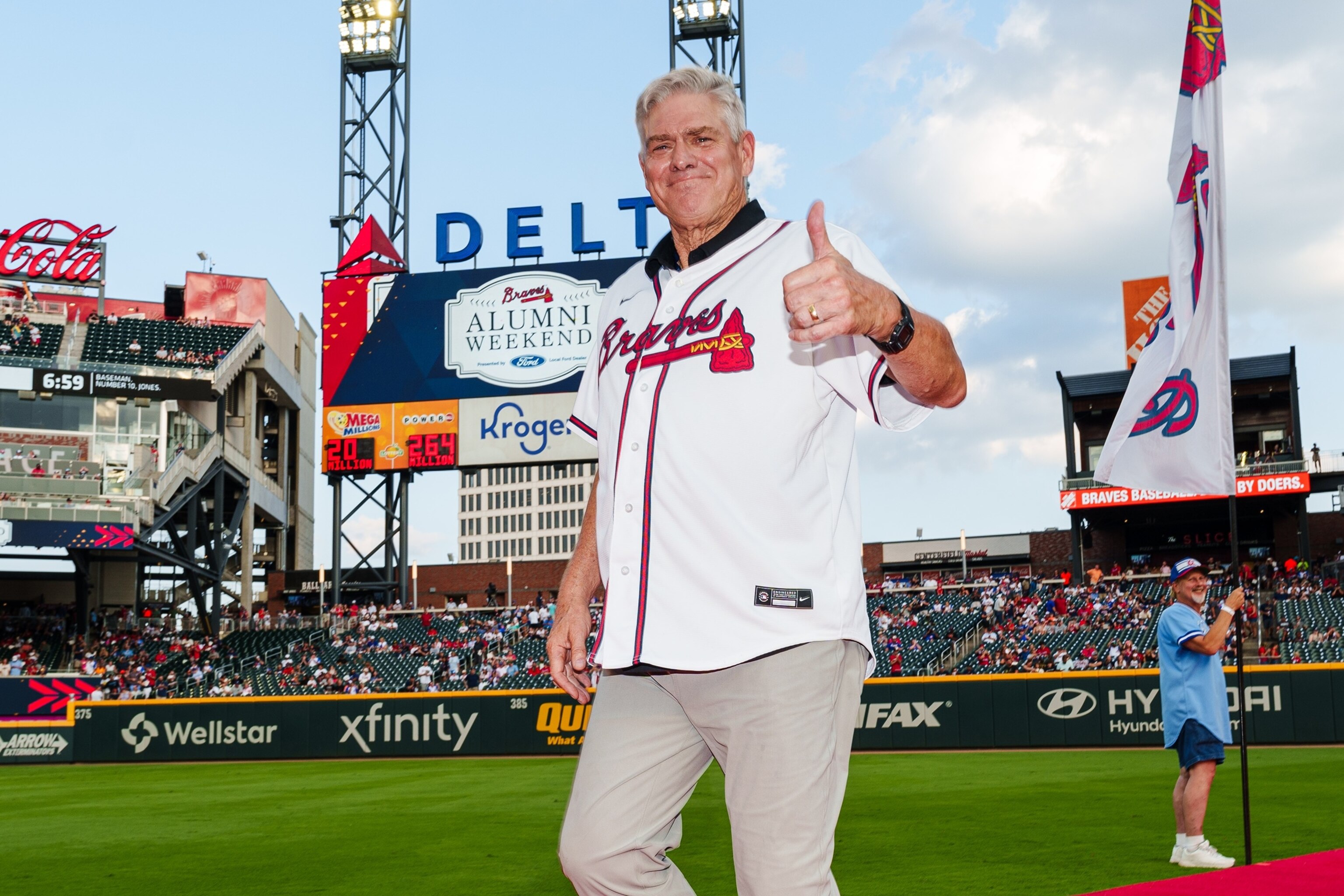

Dale Murphy during the alumni weekend red carpet roll call before the game against the San Francisco Giants at Truist Park, Aug. 18, 2023, in Atlanta.

Matthew Grimes Jr./Atlanta Braves/Getty Images

As his achievements faded from collective baseball memory, I connected with him as an adult — first on Twitter, then in real life. We met for milkshakes, and the first time I went to shake his hand, he gave me a hug.

He again signed the ball he’d first autographed when I was 12 — the initial signature having long faded from proud, sunlit display in my childhood bedroom. I had the rare privilege of getting to know my hero and becoming his friend.

We saw each other a few times over the years. This past summer, at an event the Murphys host for fans periodically in Atlanta, I fell into conversation about what it might take to get him inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame.

The Murphys dislike the question, in part because there’s no easy answer. Getting elected requires the support of at least 75% of voters — a threshold familiar to political reporters as the number of states needed to ratify an amendment to the U.S. Constitution. (That’s happened only 27 times. There are 351 members of the Baseball Hall of Fame — out of more than 21,000 men who have played in the MLB.)

For Murphy, whose time on the writer’s ballot expired more than a decade ago, it means getting the support of at least 12 out of the 16 members of this year’s Era Committee — the latest iteration of what was once known as the Veterans Committee — formed to consider players whose main contributions came from the ’80s on. Each committee member can vote for no more than three, but doesn’t have to use all of his or her votes.

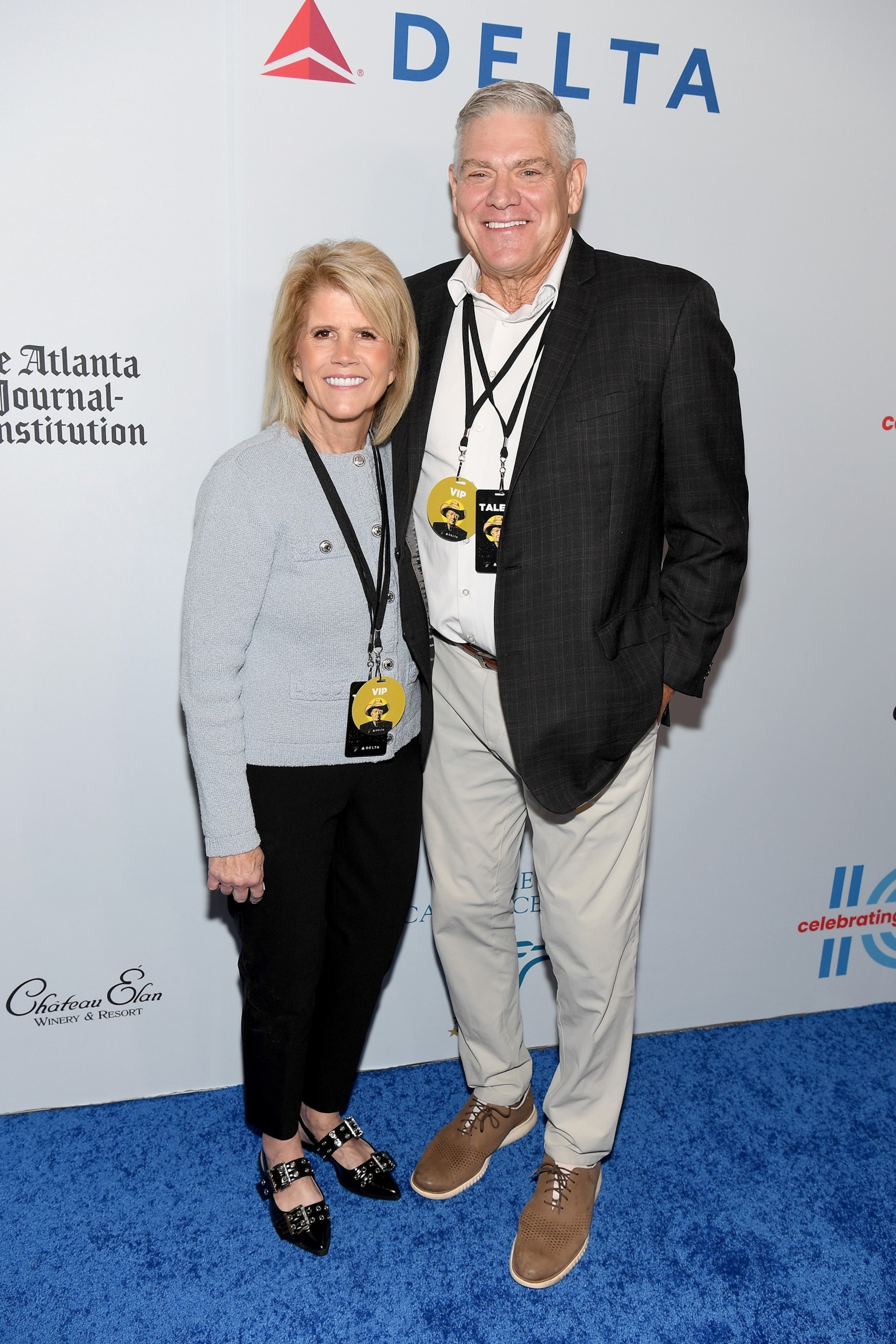

Nancy Murphy and Dale Murphy attend Jimmy Carter 100: A Celebration in Song at The Fox Theatre, Sept. 17, 2024, in Atlanta.

Paras Griffin/Getty Images

Well in advance of this Sunday’s vote, Generation Murph got to work.

Wright Thompson — a prominent Southern author who is a senior writer for ESPN, which, like ABC News, is owned by The Walt Disney Co. — wrote the script for a launch video announcing the MurphyToTheHall website.

It was narrated by the country music star Jason Aldean — another Murphy superfan. Then came three more videos featuring the sports broadcaster Ernie Johnson, whose father, Ernie Sr., was the longtime broadcast voice of the Braves on TBS.

A prominent Georgia public-relations firm urged fans to send letters to the Hall. The Georgia Sports Hall of Fame put together a statistical analysis to make the argument that a back-to-back MVP, seven-time all star, five-time Gold Glove winner who led the league in homers twice and RBIs two other times belongs in the Hall.

The launch video was retweeted by three governors (Brian Kemp of Georgia, Spencer Cox of Utah, and Ron DeSantis of Florida), a congressman (Rep. Ro Khanna of California), and also Larry the Cable Guy — united by the notion that Murphy belongs in Cooperstown.

“House of Cards” actor Michael Kelly posted a video recalling how Murphy, at the height of his fame, played backyard ball with neighbor kids like Kelly himself. REM bassist Mike Mills re-upped his jam of a plea to let Murphy in the Hall — “To the Veterans Committee,” recorded more than a decade ago with his side band, “The Baseball Project.”

Michael Kelly and Dale Murphy greet each other during the Celebrity Softball Game as part of 2025 MLB All-Star Week at Truist Park, July 12, 2025, in Atlanta.

Matthew Grimes Jr./Atlanta Braves/Getty Images

When TMZ caught up with the rapper Killer Mike last month to ask him about OutKast being added to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, he responded by saying it’s time for Murphy to get into baseball’s Hall.

Then came prominent sports voices — Hall-of-Famer Chipper Jones, Bob Costas, Ed Werder, Keith Law of The Athletic. The famous-on-Twitter @Super70sSports rallied his followers, as did the TikTok baseball influencer Brooke Knows Ball, plus sports artists including Daniel Jacob Horine and Scott Hodges.

“His reputation as a baseball player and as a person is as spotless as any baseball player that I have covered over the last 45 years,” writer and ESPN baseball analyst Tim Kurkjian told “Nightline.” “I’m not allowed to root for anything, but on a special ballot that will be held on Sunday, to me, Dale Murphy should go into the Hall of Fame.”

Rick Klein and retired baseball outfielder Dale Murphy are seen at Truist Park, ballpark of the Atlanta Braves, in summer 2024. Murphy spent most of his career playing for the Braves.

Rick Klein/ABC News

On MLB Network last month, in a segment titled “Cooperstown Justice,” anchor Brian Kenny praised the “complete player” that Murphy was.

“Dale Murphy was the man,” Kenny said. “The Hall of Fame is about greatness — the peak. And it’s supposed to be about something that we call sporting character. In both cases, Dale Murphy exceeds the Hall of Fame level. The Hall will be better with Dale Murphy in it.”

Others on the ballot this year include Barry Bonds and Roger Clemens, who would both surely have been enshrined years ago if not for their connections to performance-enhancing drugs. There’s also, among others, Don Mattingly and the late Fernando Valenzuela, who, like Murphy, claim contributions to the game far greater than statistics alone suggest.

Hall selection is inherently subjective; maybe all eight men on this year’s Era Committee ballot should and will get in eventually, and maybe none will. All have their backers and their fans, as they should.

My job covering politics has taken me to Iowa dozens of times, but until last summer I had never been to the Field of Dreams site. That changed when I signed up for a Murphy event in Dyersville, Iowa; it was built, and I would come.

I had lost my father — Stu Klein, the basketball-coaching, baseball-loving dad who took my brother Joel and me out of school for Yankee opening days, who taught us to catch and throw and keep score — the previous summer.

Those memories rushed back when I saw the bright baseball field carved out of crops. I thought of my own family, including my wife and two sons who love baseball, if not the Yankees, and even our pet rescue dog — whose name is, yes, Murphy.

ABC News’ Rick Klein and baseball legend Dale Murphy share a moment at the Field of Dreams in Dyersville, Iowa, in 2024.

Rick Klein/ABC News

Then, on a perfect summer evening, I had a catch up with my childhood hero. Cheerily and campily, Dale Murphy and I walked out of the cornrows onto the field together, just like Ray Liotta’s Shoeless Joe Jackson.

As the sun set over leftfield and the Iowa corn a few moments later, I took in the scene overlooking the very real baseball diamond built for Hollywood purposes by Kevin Costner’s Ray Kinsella, who finally had that catch with his late father.

“Field of Dreams” debuted as the ’80s came to a close. It was a fairytale, baseball purists scoff, though I’ve always known that being a fan at all means believing in stories.

I could hear the iconic line from James Earl Jones’ Terence Mann in my head.

“This field, this game — it’s a part of our past, Ray. It reminds us of all that once was good, and it could be again. Oh, people will come, Ray. People will most definitely come.”

This Sunday, when voters gather for the secret ballot that will determine baseball immortality, with rules more Byzantine than any Iowa caucus, I will be more nervous about an election than ever before.

ABC News’ Rick Klein and his family spend time with former MLB player Dale Murphy at Murph’s restaurant in Atlanta.

Rick Klein/ABC News

Both Murphys allow that they will be anxious. But having been through the drill of voting and fan and family disappointment before, they think differently about legacy at this stage of their lives — grounded, as ever.

“People will remember him as an incredible ball player but mostly as an incredible human being, and he’s a wonderful father, grandfather, husband,” Nancy Murphy said.

Dale will turn 70 in March. Whether or not this part of the journey ends with another summer evening, this time in Cooperstown, he considers himself beyond lucky. This fan feels the same.

“There’s parts of your life that are going to last forever. And that’s your relationships and your family and your kids,” Dale told ABC. “When I was in my late 20s, I didn’t think I’d ever be done playing baseball. But it ended up going by pretty fast. I’m grateful for those chances and that opportunity, but [also] to be able to think and remember about those things that are most important in life.”

Leave a Reply