When psychologist James Gibson introduced the concept of “affordances”—or the opportunities for action that the environment offers an animal—he proposed something rather radical: that perception cannot be understood without considering the inseparable relationship between an animal and its surroundings. The world, in his view, is not merely observed by an organism; it is experienced from that organism’s vantage point, through a continuous interaction between its body, its senses and its environment.

This ecological view of perception has long influenced psychology and ethology, and it is now finding renewed relevance in neuroscience. Researchers are increasingly realizing that studying brains or behaviors in isolation from their ecological context yields limited insights—an awareness that has given rise to “ecological neuroscience.” According to this perspective, understanding an animal’s brain depends on understanding the animal’s world—its physical environment, its typical movements and the sensory experiences these generate.

Many neural peculiarities that once seemed puzzling begin to make sense when viewed through this lens. For instance, cross-species differences in visual processing, such as uneven allocation of neurons to particular visual features (including color coding in the retina and V1) or asymmetries in visual field specialization, often reflect the specific demands of an animal’s ecological niche. What once looked like arbitrary quirks of anatomy or function may instead reveal how evolution has tailored each brain to perceive and act efficiently within its unique environment. As vision scientist Horace Barlow famously wrote in 1961, “A wing would be a most mystifying structure if one did not know that birds flew.”

If we accept this, then a natural conclusion follows: To understand animal behavior and brain function, we must be able to see the world as the animal does. Reconstructing an animal’s ecological niche from its own perspective is essential. And here, generative artificial intelligence may offer an unprecedented opportunity; by creating virtual worlds, it provides a new way to see, simulate and hypothesize about how animals experience their environment. In doing so, it could help bridge the long-standing gap between perception and environment—the very gap Gibson gestured toward when he insisted that the animal and its environment form a single, inseparable system.

T

he relationship between neuroscience and AI, particularly in vision research, already illustrates the value of this ecological turn. Artificial neural networks trained on large datasets have become powerful models of visual processing. The success of artificial neural network models of the primate ventral visual pathway (which is responsible for object recognition) was largely driven by ImageNet, a vast dataset of natural images that approximate what humans typically see. Combined with deep learning, ImageNet revolutionized both computer vision and computational neuroscience, demonstrating that models trained on ecologically valid data could mirror key aspects of biological vision.

Yet that success also revealed the dataset’s limits. ImageNet reflects the visual artifacts of human life—photographs that are framed, curated and captured from a distinctly human vantage—but not the embodied visual experience of humans moving through the world. These are static snapshots of how humans look at the world, not how they see and act within it. As models trained on such data reached performance plateaus, the gaps between their internal representations and neural data became increasingly apparent. Differences in perceptual robustness, invariance and behavioral generalization all point to the same conclusion: Something essential about natural visual experience is missing.

One possibility is that what’s missing is ecology: the dynamic, embodied interaction between a moving animal and its environment. ImageNet presents static images, but real-world perception unfolds over time, shaped by self-motion and continuous feedback between movement and sensory input. A frog’s visual world is defined not by still images of flies but by the visual motion patterns of prey against foliage, combined with the frog’s own leaps and gaze shifts. Understanding perception thus requires capturing the animal’s ecological experience: how sensory input, movement and environment co-evolve.

The sensory statistics an animal encounters are shaped by three factors. First is the environment itself; the visual world of a city-dwelling human, a desert lizard and a forest bird differ profoundly in structure, texture and dynamics. Second is the animal’s physical form; a rat, with its small stature and side-facing eyes, perceives the forest from near the ground, prioritizing motion and peripheral awareness over fine depth perception. A monkey, by contrast, views the same world from a higher vantage point with forward-facing eyes that afford greater binocular overlap and visual acuity. Even within the same environment, these physical differences yield profoundly different visual experiences. Third is the animal’s movements; the behavioral repertoire—the characteristic ways an animal explores and navigates—shapes what sensory input it samples. Madineh Sedigh-Sarvestani’s ongoing work, for example, compares rats and tree shrews, which have comparable body sizes but strikingly different movement patterns—the rat’s exploratory, ground-level trajectories contrast with the tree shrew’s rapid, arboreal darting. These distinct behaviors lead to vastly different visual experiences, even within similar physical environments.

Together, these elements form the ecological niche—namely, the dynamic relationship between the animal and its world. Capturing this triad experimentally, however, is extraordinarily difficult. Measuring naturalistic sensory input alongside continuous behavioral and environmental data in real habitats remains one of the grand challenges of neuroscience.

H

ere is where the new wave of generative AI offers something transformative. Recent advances in video and multimodal generative models—particularly diffusion-based systems—make it possible to create rich, dynamic and controllable visual scenes (even with real-time interaction). Within these models lies an immense diversity of real-world imagery and physical dynamics, distilled from countless visual recordings of our world. Just as large language models have been described as “cultural and social technologies,” generative video models can be viewed as “visual technologies”: repositories of the world’s collective visual imagery.

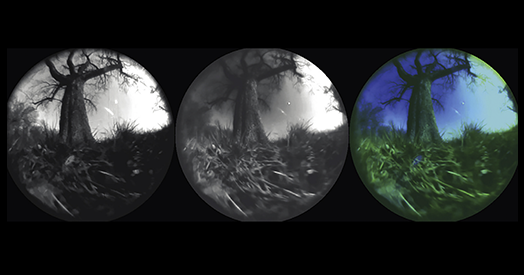

Crucially, these models can be guided. Researchers can specify what the scene should contain—through text, images or environmental snapshots—and simulate movement through that environment by controlling the virtual camera’s trajectory. The convergence of several AI advances makes it possible, for the first time, to generate video streams that approximate how the world might look from the perspective of a moving animal. Descriptions from decades of ethological research, meticulous field notes and behavioral studies can provide the textual prompt. Static images of habitats can serve as visual anchors. Camera-controlled video generation can then recreate the animal’s likely sensory stream as it moves, turns and interacts with its world.

Leave a Reply