(The Quint has consistently been the leading news organisation breaking stories on communal violence and hate crimes and carrying out in-depth investigations on communal issues. These investigations involve a lot of work and often come at great personal risk to our reporters who are on the ground. We need your support as we continue to bring out more such investigations and voices from the ground. BECOME A MEMBER and support us.)

There is a specific kind of silence that descends upon a Muslim household when the world outside catches fire. It is not a peaceful silence, nor is it the quiet of contemplation. It is a heavy, suffocating stillness, born of the collective instinct to become invisible. It is the silence of a held breath, a suspended heartbeat. I first heard that silence on 6 December, 1992.

I was five years old. We were living in Gaya, Bihar, a town where history lay thick in the dust. Buddha’s enlightenment, Hindu piety, and Muslim heritage coexisted there in a chaotic, ancient harmony. At that time, my father was not yet the officer he would later become; he was a clerk at Vijaya Bank. He was a man of modest means and immense dignity, a man who believed in the ledger of life as much as the ledgers at his desk. He believed that if you worked hard, played by the rules, and educated your children, India would reward you.

My world was small, secure, and delightfully mundane: the comforting hum of my mother, a homemaker who anchored our lives with the rhythm of her cooking; the playful hierarchy of siblings, with my brother, a year and a half older, and my sister, four years my senior, serving as my guides to the mysteries of childhood.

I watched the adults. Their faces were illuminated by the blue light of the screen, etched with a horror I couldn’t comprehend. I did not understand the word “Kar Sevak.” I did not understand “Babri Masjid.” I certainly did not understand the geography of Ayodhya. What I understood was fear.

I saw it in my father’s eyes. This man, whom I associated with the steady reliability of starched shirts and the smell of ink, looked suddenly diminished. He was no longer just a provider; he was a man keenly aware of his vulnerability. He paced the room, not saying a word, but his silence screamed. My mother held us, her grip tighter than usual, as if she could physically hold us back from a future that had suddenly darkened.

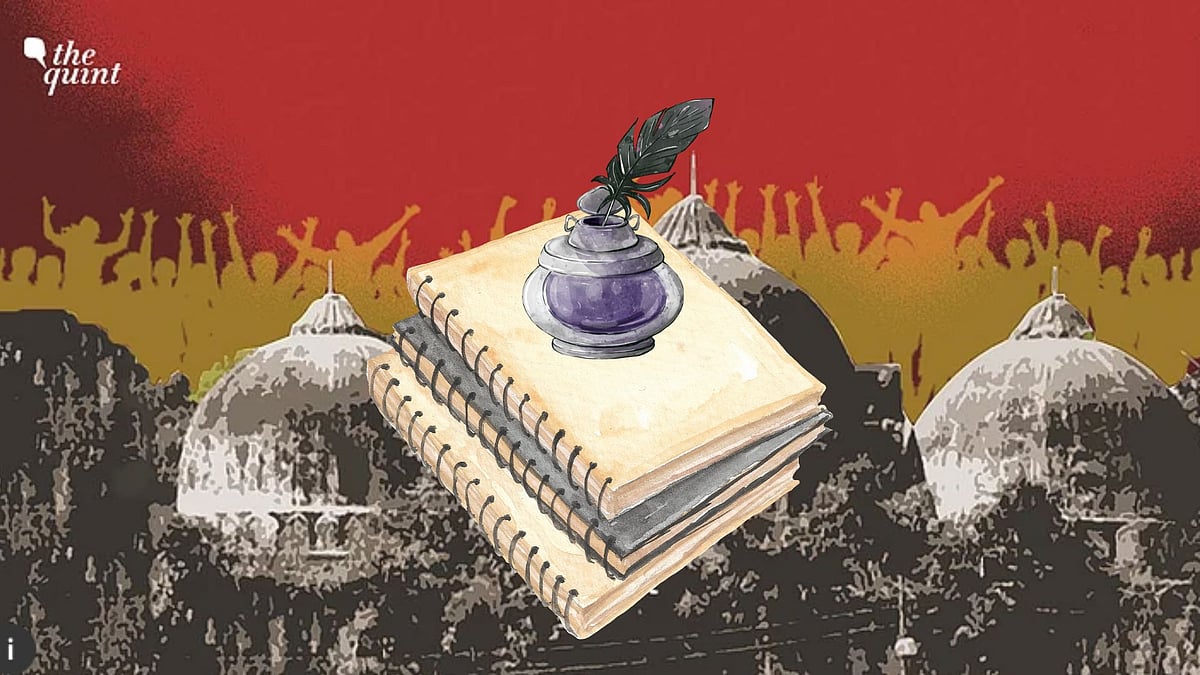

Outside, the air in Gaya felt charged. Rumors flew faster than the wind. “They are coming,” someone whispered. “Curfew,” said another. At five, I witnessed the dismantling of a structure I had never seen, but I also witnessed the dismantling of my father’s certainty. I didn’t know then that the falling domes were the opening notes of a dirge for the India my forefathers had envisioned. I only knew that something broke that day. A glass ceiling of safety shattered, and we were suddenly walking on the shards.

That evening marked the beginning of a dismantling that would continue for the next thirty-three years. Not just of a mosque, but of a dream.

Leave a Reply